Designing Residential and Datacenter Proxy Pools That Stay Stable Under Real Traffic

You wire up a new proxy pool, tests all pass, and a small batch of accounts runs smoothly.

Once real traffic hits, a different story appears:

– Latency goes up and down without a clear reason.

– Certain accounts start hitting captchas and soft blocks in waves.

– Scrapers slow to a crawl whenever you raise volume.

You switch providers, add more IPs, change rotation logic… and the pattern repeats.

The problem usually isn’t “bad proxies”. It’s that residential and datacenter exits are thrown into one noisy pool, with no clear roles, no per-task rules, and no structure around load. This article shows how to redesign those pools so they stay stable when you push real traffic, not just in tiny test runs.

We’ll cover:

- Why mixing residential and datacenter exits randomly causes fragility.

- How to split pools by task, risk, and region.

- How to handle rotation and health without collapsing under load.

- A simple layout a new team can copy.

1. The real pain: same IPs, different behavior at scale

On day one:

- You validate a few endpoints through the new proxies.

- Everything looks fast and clean.

- A handful of accounts log in, scrape, and post without problems.

Once you scale:

- The same IPs that felt “fast” now show timeouts and retries.

- Datacenter exits start getting rate-limited and return 429/5xx bursts.

- Residential exits that held accounts fine during warm-up suddenly see more verifications.

From the platform’s perspective, nothing changed about the IPs.

From yours, they suddenly “got worse”.

What actually changed is how you use them:

- Residential and datacenter IPs carry traffic they’re not suited for.

- All tasks (login, posting, scraping, reports) share the same exits.

- Concurrency explodes on certain nodes, while others sit idle.

So the goal is not “find the perfect IP range”. The goal is:

Give each type of IP a specific job, pair that with sane rotation and concurrency,

so traffic remains predictable and boring even when you grow.

2. Residential vs datacenter: different tools, different jobs

First, be explicit about what each IP type is good at.

Residential proxies

- Look like normal home or mobile users.

- Better tolerated for logins, payments, profile edits, and long-lived sessions.

- More expensive and often fewer in number.

- Slower than good datacenter lines, but safer for identity-related traffic.

Use them to hold account identity, not to pull large amounts of raw data.

Datacenter proxies

- Come from cloud or hosting providers.

- Fast, cheap, and easy to scale.

- More likely to be rate-limited or flagged if you behave like a bot.

Use them to carry volume: scraping, monitoring, reporting, search, etc.

The first structural rule follows immediately:

Residential = “who this account is”.

Datacenter = “how much data you pull”.

Once you accept that, pool design gets simpler.

3. Split pools by task, not just by type

Instead of “one residential pool” and “one datacenter pool”, define task-based pools that each have a clear purpose.

Think in three layers:

- Identity pools (residential-heavy)

- Logins.

- Password changes.

- Payment and billing edits.

- Appeals and recovery flows.

- Activity pools (mixed, but still careful)

- Posting content.

- Commenting, liking, following.

- Editing profile fields that are not highly sensitive.

- Volume pools (datacenter-heavy)

- Scraping public pages and listings.

- Pricing and ranking monitors.

- Bulk reporting and analytics queries.

Each pool:

- Has a known list of exits.

- Serves only one kind of job.

- Has its own rotation and concurrency rules.

When something goes wrong, you know which pool is noisy, instead of blaming all proxies at once.

4. Rotation and load: keep each pool boring and predictable

Random IP per request may feel “safer”, but it amplifies noise.

Stable pools need predictable rotation and strict load caps.

Inside each pool:

- Rotate per session or per batch, not every request.

- Keep each account on a small, stable subset of exits in the identity and activity pools.

- In volume pools, rotate per batch size (for example, every 500–1000 URLs).

For each exit:

- Cap requests-per-second and concurrent sessions.

- Track error rates and response times.

- If an exit starts timing out or returning many 4xx/5xx, take it out of rotation, don’t just keep hammering.

This way:

- Identity pools look like a handful of normal users using stable networks.

- Activity pools look like slightly busier users, but still believable.

- Volume pools are where you accept harsher limits and tune around them.

5. Newbie example: 30 accounts, mixed residential + datacenter

Imagine you have:

- 30 accounts on a single platform.

- 15 residential exits.

- 40 datacenter exits.

You need to:

- Log in and maintain the accounts.

- Post some content and small edits daily.

- Run steady scraping of product pages and stats.

Here’s a simple structure you can adopt:

5.1. Define three pools

- POOL_ID_RES (Identity)

- 10 residential IPs.

- Only used for: logins, password changes, payment updates, appeals.

- POOL_ACTIVITY_RES (Activity)

- 5 residential IPs.

- Used for daily posts, profile tweaks, light interaction.

- POOL_SCRAPE_DC (Volume)

- 40 datacenter IPs.

- Used only for scraping and heavy reporting.

5.2. Map accounts to exits

For the 30 accounts:

- Split them into 10 groups of 3.

- For each group:

- Pick 1 primary and 1 backup IP in POOL_ID_RES for identity.

- Pick 1 primary IP in POOL_ACTIVITY_RES for posts and small edits.

Rules:

- Each account always logs in through its primary identity IP.

- Only switch to the backup identity IP after repeated network failures, not after the first glitch.

- All scraping tasks are run through POOL_SCRAPE_DC and never touch identity IPs.

5.3. Rotation and concurrency

- Identity pool:

- No rotation during a login session.

- Limit each IP to a small number of concurrent logins (for example, 3–5 accounts at a time).

- Activity pool:

- Optional rotation between a small set of IPs per account, but only between sessions, not mid-session.

- Scrape pool:

- Assign each batch of N URLs to a single datacenter IP.

- Limit per-IP concurrency and add a backoff if errors surge.

Even this simple layout will usually feel much more stable than “one big pool plus random rotation”:

accounts stop sharing fate with scrapers, spikes localize to the volume pool, and residential exits stop burning out as quickly.

6. Where YiLu Proxy fits into this design

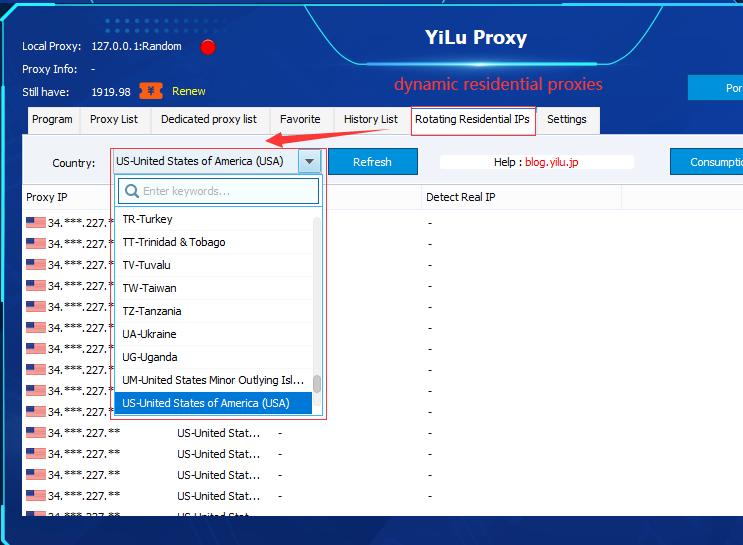

Once you start thinking in identity, activity, and volume pools, you need a proxy provider that doesn’t fight that structure. This is where YiLu Proxyfits nicely: you get residential, datacenter, and mobile IPs under one roof, and you can group them into clear tags such as POOL_ID_RES, POOL_ACTIVITY_RES, and POOL_SCRAPE_DC. That makes it easy to wire your code to pool names instead of raw IP lists, swap nodes without touching business logic, and reserve the cleanest residential exits for long-lived accounts while letting datacenter ranges handle scraping and reports. In practice, that means fewer surprises when you scale traffic, and far less time chasing “mystery instability” that’s really just bad pool design.

7. Why this design survives real traffic

A proxy pool that survives real traffic has three traits:

- Clear roles

- Residential exits carry identity and sensitive workflows.

- Datacenter exits carry volume.

- No pool is forced to be “everything for everyone”.

- Task isolation

- One misconfigured scraper script only hurts the volume pool.

- It doesn’t take login stability down with it.

- Predictable behavior under load

- Rotation patterns are structured, not chaotic.

- Concurrency is limited per exit and per task class.

- Health checks remove bad exits instead of amplifying their damage.

Once you design pools around tasks and risks instead of “how many IPs do I have”, you can grow traffic without your stack collapsing every time you push harder. The same residential and datacenter proxies suddenly feel “better” not because they changed, but because you finally gave them the right jobs.