When One Proxy Layer Isn’t Enough: Splitting Traffic by Risk Level, Not Just IP Type

Everything looks normal at a glance. Requests are flowing, proxy latency is stable, and no single IP pool appears exhausted. Yet results keep deteriorating in ways that are hard to pin down. Certain actions fail far more often than others. Some accounts decay quickly, while others survive under nearly identical automation logic. Adding more IPs or tuning rotation barely changes the outcome.

This is the real pain point: the system doesn’t break cleanly. It degrades unevenly and unpredictably.

The root cause is rarely IP quality. It’s structural. A single proxy layer is being forced to carry traffic with very different risk profiles, allowing risk to leak across tasks. The fix is not “better IPs,” but a better split: traffic must be separated by behavioral risk before IP type is even considered.

This article addresses one clear problem: why a flat, single-layer proxy architecture fails under mixed-risk traffic, and how to redesign it so different tasks stop sabotaging each other.

1. Why IP Type Fails as the Primary Control Layer

Most proxy stacks are organized around IP categories. Residential IPs handle sensitive actions, datacenter IPs handle bulk work. On paper, this looks clean and logical.

In reality, it rests on a false assumption: that traffic within one IP category behaves similarly.

1.1 Behavior, Not IP Labels, Drives Detection

A login attempt, a password reset, and a simple account page refresh can all pass through the same residential exit while producing completely different signals to the platform.

Modern detection systems do not evaluate requests by IP label. They evaluate behavior: request sequence, timing, failure patterns, retries, and state transitions.

When high-risk and low-risk behaviors share the same exits, those exits inherit the worst signals. The IPs get blamed, but the architecture is what actually failed.

2. What “Risk Level” Really Means

Risk level is not about how aggressive your script feels internally. It’s about how much attention a failure draws from the platform’s perspective.

2.1 Low, Medium, and High Risk Behave Differently

Low-risk traffic is typically read-only and stateless. Repetition and retries look unremarkable.

Medium-risk traffic depends on sessions, cookies, and navigation continuity. Mistakes here begin to accumulate signals over time.

High-risk traffic changes identity or value: logins, verification steps, password changes, payment actions, security settings. Failures in this category are rarely ignored.

2.2 Why Mixing Risk Creates “Random” Failures

When all three categories share one proxy layer, retry and routing logic designed for low-risk traffic magnifies the visibility of high-risk behavior. What looks like randomness is actually amplified signal leakage.

3. What Breaks First in a Single-Layer Setup

In a mixed-risk proxy layer, the first thing to fail is isolation.

3.1 Retry Amplification and Exit Contamination

High-risk tasks naturally fail from time to time. Retry logic responds, often aggressively. Those retries pass through exits that also serve benign traffic.

Rotation reacts globally rather than selectively. Soon, exits that never handled sensitive actions begin carrying suspicious retry patterns.

At this stage, overall success rates may still look acceptable, but critical workflows quietly deteriorate. Teams respond by adding more IPs, which only spreads the same structural flaw across a larger surface area.

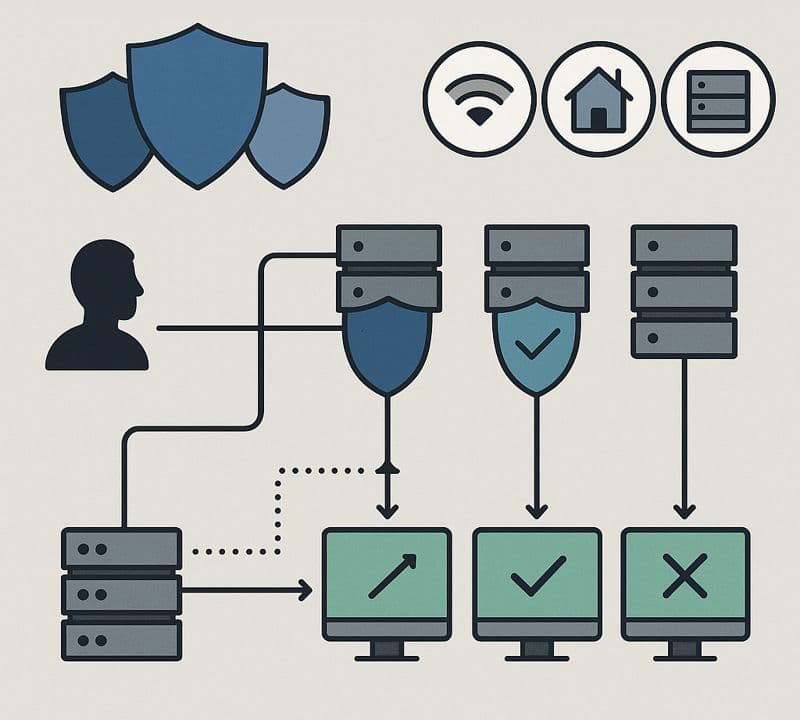

4. Splitting by Risk: The Missing Architectural Layer

The fix is conceptually simple: classify traffic by risk before choosing IP type.

4.1 Introducing Risk-Based Lanes

Instead of a single proxy layer, introduce multiple logical lanes:

- Low-risk lane

- Medium-risk lane

- High-risk lane

Each lane has its own exit pools, retry policies, and concurrency limits. IP type becomes an internal choice within each lane, not the organizing principle.

This change alone prevents contamination. Failures in the high-risk lane no longer pollute exits used for low-risk work.

5. A Practical Layout You Can Copy

The following structure works even for small teams.

5.1 Step One: Classify Tasks

- LOW_RISK: public page fetches, price lists, non-account scraping

- MEDIUM_RISK: logged-in browsing, posting, pagination, normal interactions

- HIGH_RISK: logins, verification, password changes, payment-related actions

5.2 Step Two: Define Proxy Lanes

LOW_RISK_LANE:

- Datacenter or lower-cost residential exits

- High concurrency

- Fast rotation

- Aggressive retries permitted

MEDIUM_RISK_LANE:

- Residential exits only

- Session-aware routing

- Moderate concurrency

- Limited retries

HIGH_RISK_LANE:

- Small, stable residential exit set

- Very low concurrency

- One exit per session

- Minimal or no retries

Routing logic selects the lane first, then an exit within that lane. This single rule dramatically improves stability.

6. Where YiLu Proxy Naturally

Once traffic is split by risk, the role of the proxy provider changes. You are no longer asking rotation to compensate for mixed behavior. You are asking the infrastructure to support clean separation.

YiLu Proxy fits this model without friction. It provides residential and datacenter routes under one control plane, making it straightforward to maintain distinct pools for different risk lanes.

Small, stable residential pools support high-risk workflows. Broader residential pools handle medium-risk activity. Cost-efficient datacenter pools power bulk, low-risk tasks.

YiLu Proxy does not solve risk for you, but it enables a structure where correct behavior is not undermined by the tooling.

7. How to Tell If Your Stack Is Still Too Flat

Before adding IPs or switching providers, ask a few direct questions:

- Do login flows and bulk scraping ever share exits?

- Do high-risk and low-risk tasks follow different retry rules?

- Can a failing workflow degrade unrelated traffic?

If any answer is yes, the problem is not IP quality. It is architectural flatness.

8. The Payoff of Risk-Based Separation

When traffic is split by risk, proxy infrastructure becomes predictable. Failures stay local. Metrics begin to reflect reality.

Teams stop chasing “cleaner IPs” and start controlling behavior instead.

At that point, having more than one proxy layer is not overhead. It is what allows the system to scale without relying on luck.