Rotation, Concurrency, and Exit Segmentation: Engineering Proxy Flows That Don’t Collapse at Scale

You start with a neat setup: one proxy provider, a rotation script, a handful of workers.

Small tests fly, logs look clean, and everything appears “production ready”.

Then real traffic hits:

– Latency spikes and drops with no obvious pattern.

– Some accounts suddenly drown in captchas while others stay fine.

– Scaling workers from 5 to 20 turns the whole stack into a guessing game.

It feels random, but it usually isn’t. Most of these “mystery failures” trace back to three knobs you actually control:

- How you rotate exits.

- How you run concurrency.

- How you segment exits by job.

This article has one concrete goal:

Turn rotation, concurrency, and exit segmentation into deliberate design,

so that adding traffic stops quietly destroying stability.

1. The real pain: “it only breaks when we scale”

Let’s pin down the pain points:

- At low volume, error rates are near zero. At higher volume, timeouts, 429s, and 5xx cluster around certain actions.

- Risk checks and extra verification prompts appear in waves, usually right after you speed up a job.

- Some exits are hammered nonstop while others stay almost idle, even though rotation is “random”.

- When something breaks, logs say “proxy error” but you have no idea which task pattern or exit pool is responsible.

Most teams react the same way:

- Buy more IPs.

- Add more randomness to rotation.

- Blame the provider whenever there’s a bad day.

In practice, the deeper problem is structural:

- Rotation is too fine-grained and chaotic.

- Concurrency per exit is unbounded, so peaks are brutal.

- All tasks share the same exit pool, so noise from one place spreads everywhere.

2. Rotation: not “as often as possible”, but “at the right boundaries”

Over-rotation is one of the most common invisible mistakes.

Bad patterns include:

- A new exit for almost every request.

- The same account making sensitive calls through multiple exits in a short window.

- Scrapers jumping between different regions or ASN with no business reason.

To a platform, this looks like a cluster of bots:

- One account or token appears from many networks in rapid succession.

- There is no stable “home” or consistent route for that identity.

Better rotation is about boundaries, not raw frequency:

- Rotate on session boundaries, not per call.

- Rotate per batch of work, not per URL.

- Keep each account on a small, stable subset of exits instead of a huge random pool.

For example:

- For identity-related tasks (login, profile, payments):

– One primary exit per account, plus one backup.

– A whole session sticks to that primary; only repeated network failures trigger the backup. - For scraping and reporting:

– One exit per batch of N pages (say, 500–1000).

– Next batch can use another exit, but not every single page.

Rotation should make your footprint less predictable at a global level,

but boring and coherent at the level of a single account or job.

3. Concurrency: averages are a lie, peaks are what get flagged

Teams love averages:

- “We only send 50 requests per second.”

- “Each account only does a few actions per hour.”

Risk systems do not care about your averages. They react to peaks and clusters:

- Ten accounts logging in during the same few seconds from similar exits.

- Sudden bursts of writes or posts hitting the same endpoint.

- Waves of retries stacked together after a temporary glitch.

Typical causes:

- Schedulers start all workers at the same moment.

- Daily jobs are squeezed into a narrow window “to keep things simple”.

- Retry logic hammers the same route immediately when something fails.

To fix this, you need three layers of control:

- Per-exit limits

- Cap requests per second and concurrent sessions per exit.

- Keep exits that handle sensitive actions deliberately underloaded.

- Per-account limits

- Maximum logins, posts, or other high-risk actions per account per time window.

- Cooldown periods after failures instead of instant retries.

- Temporal spread

- Start workers and accounts at slightly different offsets.

- Spread heavy tasks across broader windows instead of compressing them into one spike.

Once you introduce these controls, flags often drop without any change in provider or IP ranges.

4. Exit segmentation: stop letting every task touch every exit

Exit segmentation is about isolation:

- One noisy task should not ruin all exits.

- High-risk and low-risk traffic should not share the same identity footprint.

- Different regions or products should not all crowd onto the same addresses.

Useful axes for segmentation:

- By task type

– Identity: logins, security checks, payments, recovery.

– Activity: posting, light profile edits, normal API calls.

– Volume: scraping, monitoring, bulk reporting. - By geography

– A separate exit pool per region: US, EU, SEA, and so on.

– Accounts tied to a region rarely leave its region pools. - By platform / product

– Where possible, do not drive multiple unrelated platforms through the same critical exits.

If a noisy scraping job in one region melts down, the blast radius should stay inside that scrape pool.

It should not quietly destabilize logins for everything else.

Segmentation turns “one global disaster” into “one local incident”.

5. Newbie example: one platform, three tasks, fewer surprises

Imagine you run:

- 40 accounts on a single platform.

- Two major regions: 25 accounts for US, 15 for EU.

- 20 good residential exits and 40 datacenter exits.

You need to support:

- Stable logins and profile/payment changes.

- Daily posting and light interaction.

- Continuous scraping of public pages and stats.

A simple, effective structure:

5.1. Build three exit pool types

- POOL_US_IDENTITY / POOL_EU_IDENTITY

– Residential exits.

– Only for logins, password changes, payment updates, appeals. - POOL_US_ACTIVITY / POOL_EU_ACTIVITY

– Residential exits.

– Only for posting, small profile edits, light interaction. - POOL_SCRAPE_DC

– All datacenter exits.

– Only for scraping and heavy reporting.

5.2. Rotation rules inside pools

- Identity pools:

– Each account gets 1 primary and 1 backup exit in its region.

– A session uses only the primary. Backup is used only after repeated network failures. - Activity pools:

– Each account uses 1–2 exits for posting, rotated per session, not per request. - Scrape pool:

– Break jobs into batches (for example, 500 URLs).

– Each batch uses a single datacenter exit.

– Exits with rising error rates are paused and removed from rotation.

5.3. Concurrency and timing

- Limit how many accounts each identity exit can serve at once.

- Spread logins and posts across broader windows, with small random delays.

- Use backoff for failures instead of hammering the same path again immediately.

Even with basic tracking, this layout will:

- Localize noisy failures to the scrape pool.

- Protect identity and activity exits from collateral damage.

- Make rotation and concurrency patterns easy to reason about.

6. Where a provider like Yilu Proxy actually helps

All of this is easier if your proxy provider makes segmentation and health visible instead of hiding it.

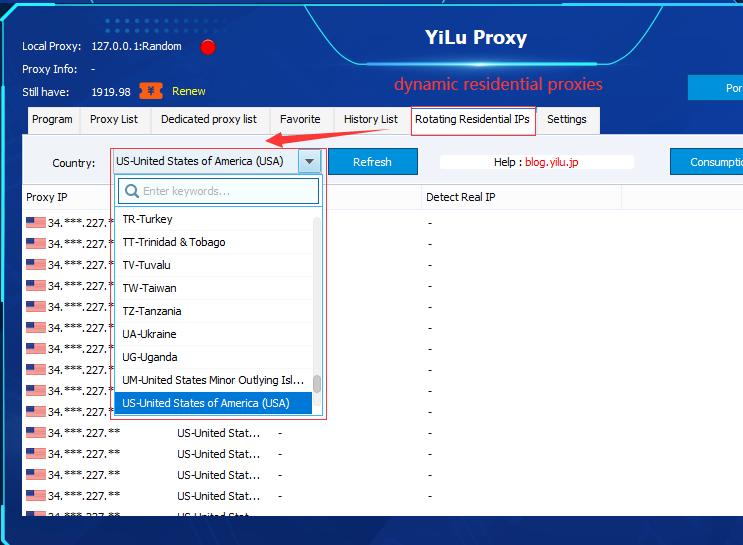

A service like Yilu Proxy gives you:

- Separate residential, datacenter, and mobile lines, so you can map identity, activity, and volume to the right type instead of forcing one pool to do everything.

- Line groups and tags, so pools like

POOL_US_IDENTITYorPOOL_SCRAPE_DCare first-class objects; your code talks to tags, not hardcoded IPs. - Latency and success metrics per node, so your health checks can automatically take sick exits out of rotation rather than discovering them only after a bad day.

- Simple access from browsers, scrapers, and automation tools, so multiple teams can share the same exit design instead of each inventing their own.

When you combine this kind of proxy layer with deliberate rotation, concurrency limits, and exit segmentation, the result is boring in the best way:

you can turn up traffic without your proxy flows collapsing every time you grow.